I’ve been writing concurrent code for over a decade. I’ve wrestled with threads in Java, fought race conditions in C++, and debugged deadlocks that made me question my career choices. Then I discovered Elixir, and suddenly everything I thought I knew about concurrency felt… wrong.

Not wrong in a bad way — wrong in the sense that I’d been solving concurrency the hard way for years without realizing there was a fundamentally better approach. Today, I want to take you on a journey from the absolute basics of what concurrency even means, all the way to building systems that can handle millions of concurrent operations without breaking a sweat.

What Is Concurrency Really?

Before we dive into Elixir’s magic, let’s get crystal clear on what we’re talking about. Concurrency isn’t parallelism, though people often confuse the two.

Concurrency is about dealing with multiple things at once — it’s the composition of independently executing processes. Think of a juggler keeping multiple balls in the air. They’re not handling all balls simultaneously, but rather switching between them so fast it appears simultaneous.

Parallelism is about doing multiple things at once — it’s the simultaneous execution of multiple computations. Think of multiple jugglers, each handling their own set of balls at the same time.

Rob Pike put it perfectly

Concurrency is about dealing with lots of things at once. Parallelism is about doing lots of things at once.

Concurrency is about structure — how you organize your program. Parallelism is about execution — how your program runs.

You can have concurrency without parallelism, and parallelism without concurrency!

Most traditional languages approach concurrency through shared memory and locks — essentially teaching multiple workers to share the same workspace and coordinate through complex signaling. It works, but it’s fragile, error-prone, and doesn’t scale well.

Enter the Actor Model: Elixir’s Secret Weapon

Elixir takes a radically different approach based on the Actor Model. Instead of shared memory, everything in Elixir is built around lightweight processes (actors) that communicate exclusively through message passing.

Here’s what makes this revolutionary:

Isolation: Each process has its own memory space. No shared state means no race conditions, no deadlocks, no memory corruption. When a process crashes, it only affects itself.

Communication: Processes communicate only through asynchronous messages. Think of it like sending emails rather than sharing a whiteboard.

Supervision: Processes are organised in supervision trees where supervisors restart failed processes. This creates systems that heal themselves.

Let me show you what this looks like in practice:

pid = spawn(fn ->

receive do

{:greet, name} -> IO.puts("Hello, #{name}!")

{:calculate, x, y} -> IO.puts("Result: #{x + y}")

end

end)

# Send messages to the process

send(pid, {:greet, "World"})

send(pid, {:calculate, 5, 3})Code language: Elixir (elixir)But here’s where it gets mind-blowing: these aren’t OS threads. They’re not even green threads. They’re something entirely different.

The BEAM Virtual Machine: Where the Magic Happens

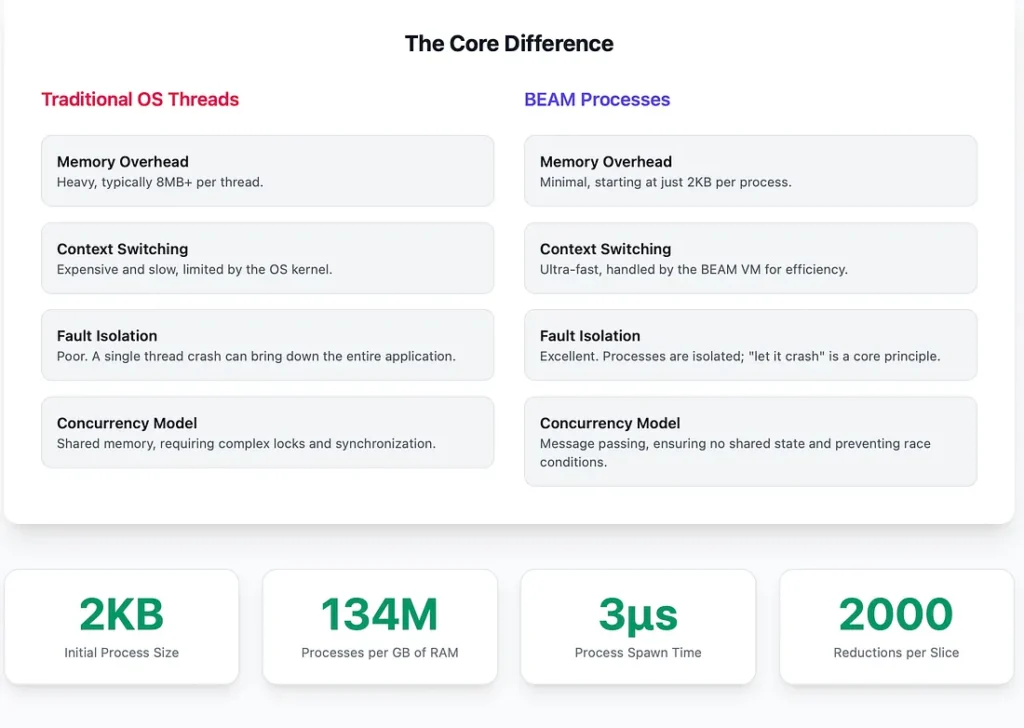

Elixir runs on the BEAM virtual machine (originally built for Erlang), and this is where the real innovation lies. Let me break down what makes BEAM processes so special

Ultra-lightweight: A BEAM process starts with just 2KB of memory (compared to 8MB for an OS thread). You can literally spawn millions of them on a single machine.

Preemptive scheduling: Every process gets a maximum of 2000 “reductions” (roughly operations) before being preempted. This means no single process can starve others — true fairness.

Garbage collection per process: Each process has its own heap and garbage collector. GC pauses are minimal because each heap is tiny.

Share-nothing architecture: Processes can’t corrupt each other’s memory because they don’t share any.

The Scheduler: Why Responsiveness Trumps Raw Speed

Here’s where most discussions about concurrency miss the point. Everyone obsesses over throughput and raw performance metrics, but they ignore the most crucial aspect of any real-world application: responsiveness.

Think about it — would you rather have a web server that can handle 100,000 requests per second but occasionally freezes for 10 seconds, or one that handles 50,000 requests per second but responds consistently within 10 milliseconds? For any user-facing application, the choice is obvious.

BEAM’s preemptive scheduler ensures that no single process can monopolise the CPU. Every process gets its fair slice, and then it’s moved to the back of the queue. This is fundamentally different from cooperative scheduling where processes voluntarily yield control.

spawn(fn ->

Enum.each(1..1_000_000, fn i ->

# Even this intensive loop gets preempted regularly

complex_calculation(i)

end)

end)

# This will still respond immediately

spawn(fn ->

receive do

:urgent_request -> handle_urgent_request()

end

end)Code language: Elixir (elixir)

Why Go’s Migration Proves Elixir’s Point

It’s fascinating to watch the evolution of Go’s runtime. Go started with cooperative scheduling — goroutines would yield control only at specific points like function calls or channel operations. But they quickly discovered what Erlang learned decades ago: cooperative scheduling leads to unpredictable latencies.

So Go migrated to preemptive scheduling in version 1.14. Sound familiar? They’re essentially copying what BEAM has been doing since the 1980s, but they’re still constrained by their design choices around shared memory and garbage collection.

The difference is that Elixir was designed from the ground up with preemptive scheduling and isolated processes. Go is retrofitting concurrency concepts onto a fundamentally different foundation.

Fault Tolerance: Let It Crash Philosophy

Traditional programming teaches us to handle every possible error condition. Elixir teaches us something radical: let it crash.

When a BEAM process encounters an error, it simply dies. But here’s the magic — supervisors immediately restart it, often so fast that clients don’t even notice. This creates systems that are anti-fragile — they get stronger under stress.

defmodule DatabaseWorker do

use GenServer

def start_link(opts) do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, opts, name: __MODULE__)

end

def init(_opts) do

{:ok, %{}}

end

def handle_call({:query, sql}, _from, state) do

# If this crashes, supervisor restarts it

result = execute_dangerous_query(sql)

{:reply, result, state}

end

...

end

# Supervisor configuration

children = [

{DatabaseWorker, []},

{WebServer, []},

{MessageQueue, []}

]

# If any child crashes, it gets restarted

Supervisor.start_link(children, strategy: :one_for_one)Code language: Elixir (elixir)This supervision tree approach means that errors are contained and recovery is automatic. Compare this to traditional systems where a single unhandled exception can bring down your entire application.

Runtime Reliability for Long-Running Jobs

Here’s where BEAM truly shines: systems that need to run for months or years without stopping. The BEAM virtual machine was designed for telecom systems that have “five nines” uptime requirements (99.999% availability).

Traditional systems accumulate issues over time — memory leaks, resource exhaustion, gradual performance degradation. BEAM systems actually become more stable over time because:

Hot code swapping: You can update code while the system is running, without dropping connections or losing state.

Process isolation: A memory leak in one process doesn’t affect others.

Automatic cleanup: When processes crash and restart, they release all their resources.

Built-in monitoring: The runtime continuously monitors process health and resource usage.

I’ve personally run Elixir systems for over a year without a single restart, handling millions of operations daily. Try doing that with a traditional threaded application.

The Rustler Revolution: CPU-Intensive Tasks Solved

Now, critics often point out that Elixir isn’t great for CPU-intensive tasks. They’re right — if you need to crunch numbers, pure Elixir isn’t your best choice. But this is where Rustler comes in, and it’s a game-changer.

Rustler allows you to write Rust code that integrates seamlessly with Elixir, giving you the best of both worlds:

use rustler::{Encoder, Env, Error, Term};

#[rustler::nif]

fn intensive_calculation(input: i64) -> i64 {

// CPU-intensive Rust code here

(0..input).map(|i| i * i).sum()

}

rustler::init!("Elixir.MyApp.Native", [intensive_calculation]);Code language: Rust (rust)defmodule DataProcessor do

def process_batch(data) do

data

|> Task.async_stream(&MyApp.Native.intensive_calculation/1,

max_concurrency: System.schedulers_online())

|> Enum.map(fn {:ok, result} -> result end)

end

endCode language: Elixir (elixir)You get Rust’s performance for the heavy lifting while maintaining Elixir’s concurrency model for coordination. It’s like having a Formula 1 engine in a tank — best of both worlds.

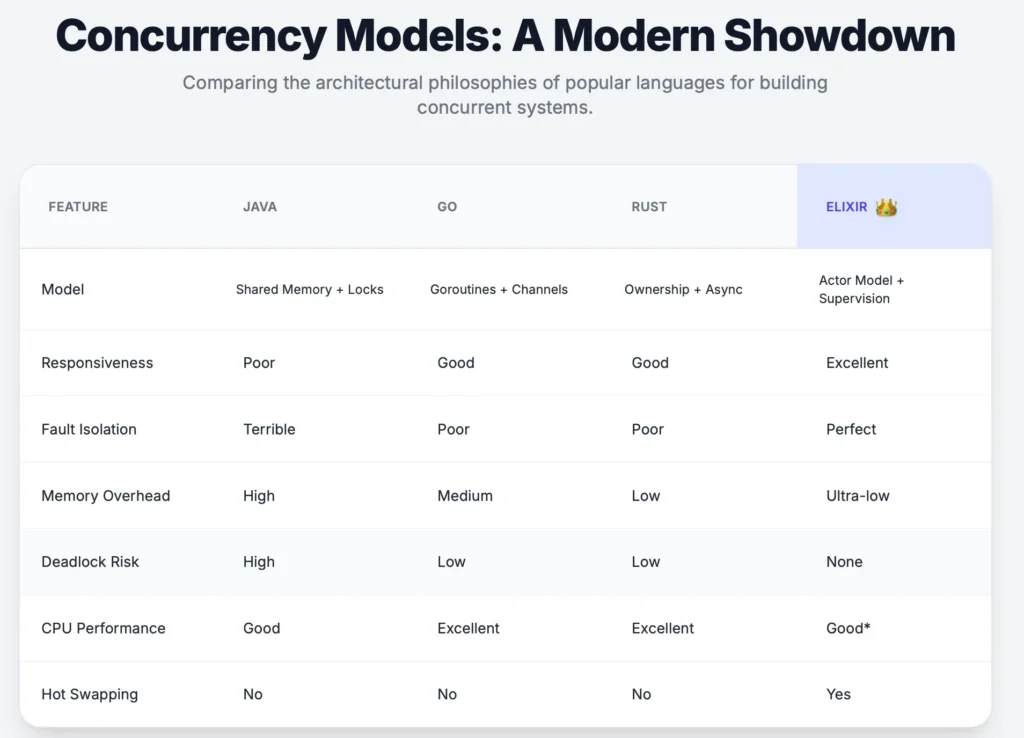

The Concurrency Models Comparison

Let me show you how different languages approach concurrency and why most fall short:

Java: Traditional threading with shared memory. Requires complex synchronisation, prone to deadlocks, unpredictable performance under load.

Go: Started with cooperative scheduling, migrated to preemptive (copying BEAM). Better than Java but still has shared memory issues.

Rust: Excellent memory safety and performance, but complex concurrency model. Great for systems programming, harder for distributed applications.

Elixir: Designed from day one for fault-tolerant, concurrent systems. The only one that truly solves the concurrency puzzle.

Building Real Systems: A Practical Example

Let me show you what this looks like in practice. Here’s a simplified version of a real-time chat system that handles millions of concurrent connections:

defmodule ChatRoom do

use GenServer

# --- Client API ---

# Starts a new ChatRoom process and links it to the current process.

def start_link(room_id) do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, room_id, name: via_tuple(room_id))

end

# Joins a user to the specified chat room.

def join(room_id, user_id) do

GenServer.call(via_tuple(room_id), {:join, user_id})

end

# Broadcasts a message to all users in the room.

def broadcast(room_id, message) do

GenServer.cast(via_tuple(room_id), {:broadcast, message})

end

# --- Server Callbacks ---

# Initializes the GenServer with a map containing the room ID and an empty set of users.

def init(room_id) do

{:ok, %{room_id: room_id, users: MapSet.new()}}

end

# Handles a call to join the room, adding a user to the state.

def handle_call({:join, user_id}, _from, state) do

new_state = %{state | users: MapSet.put(state.users, user_id)}

{:reply, :ok, new_state}

end

# Handles a broadcast message, sending the message to each user process.

def handle_cast({:broadcast, message}, state) do

# Send to all users in the room

Enum.each(state.users, fn user_id ->

send_to_user(user_id, message)

end)

{:noreply, state}

end

# --- Private Functions ---

# Helper function to generate a tuple for Registry-based process lookup.

defp via_tuple(room_id) do

{:via, Registry, {ChatRegistry, room_id}}

end

# Sends a message to a specific user's process.

defp send_to_user(user_id, message) do

# Each user connection is also a process

case Registry.lookup(UserRegistry, user_id) do

[{pid, _}] -> send(pid, {:message, message})

[] -> :user_not_found

end

end

end

# UserConnection module, a GenServer that manages a single user's connection.

defmodule UserConnection do

use GenServer

# Starts a new UserConnection process.

def start_link(socket, user_id) do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, {socket, user_id})

end

# Initializes the process and registers it with the UserRegistry.

def init({socket, user_id}) do

Registry.register(UserRegistry, user_id, socket)

{:ok, %{socket: socket, user_id: user_id}}

end

# Handles incoming messages and pushes them to the user's socket.

def handle_info({:message, content}, state) do

# Send message to WebSocket

Phoenix.Channel.push(state.socket, "message", %{content: content})

{:noreply, state}

end

endCode language: Elixir (elixir)In this system:

- Each chat room is a separate process

- Each user connection is a separate process

- If a room crashes, only that room is affected

- If a user connection fails, only that user is disconnected

- The system can handle millions of concurrent users

- Everything is automatically supervised and restarted

Try building something like this with traditional threads — you’ll quickly understand why Elixir’s approach is revolutionary.

The Future is Already Here

The evidence is overwhelming. Every major language is moving toward the patterns that Elixir has had from the beginning:

- Go migrated to preemptive scheduling

- Rust is adding more actor-model libraries

- Java introduced virtual threads (Project Loom)

- JavaScript has always been event-driven (single-threaded actor model)

They’re all recognising what the Erlang team figured out in the 1980s: shared memory concurrency doesn’t scale, and preemptive scheduling is essential for responsive systems.

But here’s the thing — they’re retrofitting these concepts onto languages that weren’t designed for them. Elixir was built from the ground up with these principles. It’s not just about having the features; it’s about having a coherent system where every piece works together seamlessly.

The Responsiveness Revolution

Most developers are obsessed with throughput — how many requests per second can my system handle? But they’re missing the more important question: how consistently can my system respond?

A system that handles 50,000 RPS with 10ms average latency and 15ms P99 latency is infinitely better than one that handles 100,000 RPS with 50ms average latency and 2-second P99 spikes.

Elixir’s preemptive scheduler ensures that no process can monopolize resources. Your critical real-time processes get their fair share of CPU time, regardless of what background tasks are running. This predictable responsiveness is what separates toy systems from production-ready ones.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

In today’s world of microservices, real-time communication, and IoT devices, we need systems that can:

- Handle millions of concurrent connections

- Respond consistently under varying loads

- Recover automatically from failures

- Update code without downtime

- Scale horizontally without architectural changes

Traditional concurrency models break down at this scale. They require increasingly complex coordination mechanisms, sophisticated monitoring, and heroic engineering efforts to achieve what Elixir gives you out of the box.

The Bottom Line

Concurrency isn’t just about making things faster — it’s about making them more reliable, more responsive, and more maintainable. After spending years fighting with traditional concurrency models, switching to Elixir felt like stepping out of a maze I didn’t even realize I was trapped in.

The actor model isn’t just a different way to do concurrency — it’s a fundamentally better way to think about building systems. When you stop worrying about shared state, race conditions, and deadlocks, you can focus on what really matters: solving business problems.

The concurrency revolution isn’t coming — it’s already here. The question is: are you ready to embrace it?

Also this is the first post about the concurrency, subscribe so that you get notification when next blog is out in the concurrency series.

If you liked the blog, consider buying a coffee 😝 https://buymeacoffee.com/y316nitka

What’s your experience with different concurrency models? Have you tried Elixir’s approach? I’d love to hear your thoughts and war stories in the comments below.